Thirty Years in Portland

My grandparents arrived in Eastern Oregon in the 1930s and raised their two daughters in various farming communities. One of them stayed, married, and has been farming around Vale since the 1950s. But one of them--my mom--decided to head off to the big city to seek her fortune. Thus was I born and raised (mostly) in Boise, Idaho. I made my way back to Oregon to attend college here, arriving when I was just a few years younger than my grandparents had been fifty years before me. That was 1986.

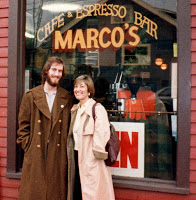

Portrait of the blogger as a young man (with mother). Circa 1987.

Portland's transformation in those thirty years (along with a surprising vein of continuity) has been radical. Our minds are built to create sense of disparate inputs, and 2016 Portland seems like an organic result of an unseen trajectory 1986 Portland traveled; when I put my mind back on what the actual town was like then, however, this 2016 seems like a near impossibility.

In the mid-eighties, Portland was a poor, rough town. Portland had 66 murders in 1987--one of the highest rates in the country (the current ten year average is 24, and the city's a good deal larger now). It felt dangerous; there were places you didn't go. It was a visibly racially divided town. A century of racist policies had concentrated black Portlanders into a section of the Northeast, a poor section neglected by the city. Crimes of all kinds routine throughout the city, and petty theft was so common I just started leaving my car unlocked so people wouldn't break the windows to get in and discover there wasn't anything worth stealing. You were lucky indeed if you managed to avoid having your car, apartment, or house broken in to. For many of us, it was a regular experience.

Unlike many larger cities elsewhere in the country, Portland was never an industrial hub, but rather the focal point for the extractive industries that dominated the state's economy until the 1970s (logging, commercial fishing, ranching, and farming). Until a few years after I arrived, you'd still see giant flotillas of Douglas fir being pulled down the river. The reason Kurt Cobain wore flannel was not because it was a proto-lumbersexual moment in music and fashion, but because he came from Aberdeen, the heart of the Washington logging industry. In Portland about half the men wore jeans and flannel, but they were work clothes, not affectations.

Portland's unusual status had positive and negative effects. As early as the 1970s, the qualities that led Portland to become Portlandia were present. It was dirtcheap to live here. A couple years after I arrived, I became a hippie artist at Saturday Market, and I lived in a group house on Clinton Street that had five bedrooms and rented for $495 a month. At one point we had seven people living there and my rent was $80 ($176 in today's dollars). This meant it was a great place to live for the young and broke. I could string beads by day and scrape together enough money to pay rent and buy a half-rack of Rainier pounders every now and again. There wasn't really an upper class in Portland, and there wasn't a restaurant in the city that would have barred someone who was in jeans. (When we'd buy new Levi's, we'd joke they were our "dress jeans.")

Portland also didn't have industrial wealth that cities like Detroit and Pittsburgh had to build symphony halls and theaters. This led to a distinctly DIY approach that has been fundamental to the city's ethos. But it also meant there wasn't a lot of money to improve the city. Small businesses were run on a shoestring in provisional spaces in buildings that hadn't been much improved in 75 years.

Of course, a lot of this affected things like breweries, which required capital startup budgets. Banks wouldn't even look at them. (Karl Ockert, founding brewer at BridgePort, famously reported that one of the banks he went to told him, "Breweries don't open, they shut down.") Fortunately, dairy equipment was cheap and plentiful, and rents were cheap. Entrepreneurs who wanted to start breweries could get off the ground with relatively small investments (usually from personal savings, family and friends). Breweries were, in this way, much like other businesses. They were started by industrious but often cash-poor entrepreneurs who strapped their breweries together with baling wire in less-desirable precincts of the city.

Changing Geography

To get a sense of how much the city's geography has changed, let's start with the warehouse district behind the Henry Weinhard Brewery on Burnside. Immediately adjacent to downtown, it was in the mid-1980s almost vacant. Warehouses filled the blocks, but the streets were empty. It was as if a catastrophe had happened and forced all the people to leave suddenly. This was, predictably, a place of cheap rents, which ultimately led to its revival as artists moved into the warehouse and created lofts. A few galleries followed, and so did a few other businesses--like the three new breweries that opened between 1984-'86.

Throughout the 1990s, city planners planned, and around the turn of the century it was rebranded "the Pearl District" and soon the wealthy began displacing the artists. In the decade and a half since, it has become the city's wealthiest enclave, a mini-Manhattan home to people with the kind of wealth no one seemed to have in the 1980s.

The Pearl District was the most dramatic change, but most of the rest of the city has transformed as well. The South Waterfront has new buildings and thousands of new residents. Gentrification has remade the neighborhoods. Places like North Mississippi and Alberta Street have been reborn

as artsy hipster enclaves. The Northeast, which was once shorthand for "dangerous," has had an influx of wealth all the way out to Woodlawn, where Breakside is located. The urban growth boundary has forced infill, and now just about every neighborhood west of 60th is welcoming (or resisting) skinny houses and apartment complexes.

The light rail system, in the mid 1980s, consisted of a single spur from downtown out to Gresham in the east. Now MAX forms a series of arteries that feed the suburbs in all directions. Streetcars, which once carried people out on the main arterial roads of the east side, have returned to the inner core. In the past decade, the city has spent millions adding bike lanes, which make travel for the blogger a snap. (Despite that, car traffic is an order of magnitude more horrible than it was even five years ago.)

Like most American cities, Portland is now larger, safer, and more diverse than it was thirty years ago. When I arrived, there were perhaps 450,000 people in town; now there are over 600,000. We are still the whitest of the big American cities, but the nonwhite population is now up over a quarter of the population. Crime, as everywhere, is down down down.

Culture and Continuity

One remarkable thing about Portland is how consistent its culture has remained throughout this entire period. For decades, Portland has been a major target of migration for other Americans, but lately it has gotten crazy. Walk into any bar in the city and ask the hundred people inside to raise their hands if they were born in Portland, and maybe two will go up. (Another few will have come from elsewhere in Oregon.) Unexpectedly, the migrants are the preservers of culture. When people decide to relocate, they take the measure of a place and how well it suits their aspirations. People who like big, cosmopolitan cities choose Seattle or San Francisco. People who like quirky, parochial small towns opt for Portland--and then they work to keep the city as it was when they moved here.

Measured by population, Portland is larger than Boston, but it has never felt that way. It feels like a small town, both because you constantly see people you know, but also because of the scale. It's drowsy and insular (I even joke that it's "the city that sleeps"). Cosmopolitan cities look up and outward, to the world. Portlanders, like small animals, keep their eyes on the ground. We look inward. That has been fantastic for developing local culture, from artisanal products (the list is endless--wine, coffee, beer, chocolate, food carts, all manner of craft) to local business. Given a choice between something made in Oregon or elsewhere, Portlanders will always choose the Beaver State goodies.

If you've even wondered why the beer scene in Portland is miles better than Seattle, this explains it. It was cheaper and easier to start a brewery in Portland than Seattle, and that in turn meant they became a thing. Having become a thing, Portlanders fell in love with them, which created a much bigger market for them than in other cities (until recently--and it may still be true--Portlanders drank more locally-brewed beer than any city in America; not per capita, in total). Portlanders, ever the miniaturists and artisans, made interesting, quirky beer, which further fed the culture of beer drinking. We have not come quite to the place Germany, the UK, and the Czech Republic have where going to the pub for a drink is the center of social activity, but we're a lot closer than anywhere else in the US. Seattle, meanwhile, looked up and out--and the same virtuous cycle that created the Portland beer scene was weaker and more diffuse up north. They like their local beer well enough--but they like ours, too. (And you can't give Washington beer away in Oregon, which is why we have so little of it.)

Finally, and importantly, doing your own thing has always been celebrated here. Whether that was starting a brewery or band, or tricking your yard out with a jungle of perennials, or developing a culture around something unique (bombing down a hill into downtown on a little bike, say), it was always greeted warmly. Even corporate types are expected to play dodgeball or roast their own coffee. And again, the people who moved here have been the kind who marvel at these activities and think it would be cool to live in a place where everyone did them.

Becoming Beervana

In 1986, there were only six breweries in Portland (one was the giant Blitz-Weinhard Brewery downtown), but the city was already getting excited about beer. It was embryonic, and people weren't sure what it even meant to be into good beer--but they were gamely trying to figure it out. Weinhard helped by introducing a specialty line that included such exotica as "Ale" and "Dark." As comical as this sounds, they were observably better beers and they helped us imagine a world in which beer might have a different color or a different taste than the one we knew. (The ale wasn't an ale, but that term was full of mystery and promise and I suspect helped the actual ale-brewers who came along in the 80s.)

I always regretted being a little too young to see the birth of the good beer scene here. BridgePort started selling beer in 1984, Widmer and McMenamins in '85, and Portland Brewing in '86. All of this was draft beer, and so hard for an underage drinker to access (I turned 21 in early '89). When you talk to the founders about those early days, they describe what a weird experience it was to try to sell beer to publicans who didn't know what it was. They were educating and selling at the same time. The 80s were intense early years when success was far from a given, but that uncertainty was incredibly brief in historic terms. By the time I could drink legally in a bar, Portland had mostly already become Beervana.

I credit two agents for this change. The first were the McMenamins, whose pubs multiplied like mushrooms after an Oregon rain across the city in the 1980s. They all carried McMenamins beer, and they created an almost overnight recognition that it was possible to have local beer as a regular thing. (I did start drinking McMenamins beer before '89, but that's a different story.)

The second agent was Widmer Hefeweizen. By the late 1980s, it was a smash hit commercially, and was available in scores (hundreds?) of pubs and restaurants. It was unusual-looking for a beer at the time, served in large vases with a wheel of lemon. But it was approachable in flavor, which meant near-universal appeal. Women, in particular, were happy to drink Hef, and that helped translate "microbrew" to a general audience. It became an instantly-recognizable status symbol and was for the better part of a decade the definition of local beer. These two things--an early, high-profile "it" beer and a growing empire of brewpubs--made Portland a beer town in the space of a few years.

So much has changed in these thirty years about the city, but the truth is, I don't have any memory of a time before it was associated with good beer. I would argue that beer is actually the ur-product of Portlandia, the first of the artisanal products that would come to define the city and its culture. Craft beer is in this way a metaphor for Portland. It arose because the circumstances were ripe in the city at the time (which was not unique), but flourished because of the way Portland's culture prizes indie projects, local projects, and the opportunity to do things its own way.

This post is running long, so I'll close it up here. There's so much more I could say--how we got from the Crazy 8s to the Decemberists, literary Portland, the food revolution--but this is probably adequate. The point is clear: the city has been under constant change throughout my thirty years, and yet has never stopped feeling like Portland. It's been a wonderful thirty years. In that time, I've traveled throughout Asia and Europe, and I've never found a place I'd rather live. Let's hope I get to see another thirty.