Put a beer in a man's hand and install him in a cozy corner table at the pub and his mind starts thinking--usually about beer. What is that man thinking? Read on--

Anchor was never just a brewery. The story of Fritz Maytag saving a brewery became a founding myth for American craft beer. Anchor was at once the past and the future, the proof that small breweries could exist outside an ecosystem of commodity canned lagers.

All the world wants the next IPA. The trouble is that, while they’re churning out scores of new versions every year, too few breweries have the time to dial in their beers.

I don’t expect haze to leave IPAs anytime soon—but increasingly, the term “hazy IPA” has started to seem, well, hazier.

States and regions do not develop identically to the nation. When we look at Oregon in late 2019, we find a state in a substantially different place than it was in 2010, and also a different one than other regions now. Let’s take a moment to review the defining beers of the past decade in Oregon.

When we look back in the years and decades ahead, which products will we stand out in our memories as classically from the 2010s? Here are a dozen products that tell the story of the times.

As I was preparing to leave for a month in Europe, Portland passed an important anniversary that may hold lessons both about the city’s current condition and also the state of the beer market. On September 1, 1999, the Blitz-Weinhard brewery turned off the lights for the last time.

Why do we have a more emotional connection to beer than, say, toothpaste brands? Because of evenings like these.

Media outlets are closing down by the week, and it can seem like a grim time for content-producers. But not everyone is suffering. Things are great here at Beervana, and I’d like to tell you why.

In these times of division, can’t we all just get along—over a pint, anyway?

Historian and archaeologist Alexander Langlands has a new book called Cræft, the purpose of which is to reclaim the meaning of "craft" as it existed before it became a marketing slogan or an expensive item available at boutiques. How might this apply to beer?

One should never age most beers, and the beers one ages should never be aged very long. Leave a bottle in your cellar that dates to the Clinton administration and it’s going to suck. Unless something very rare and special happens instead.

As markets become more fragmented, it becomes harder and harder to keep abreast of everything going on. The number of breweries has more than doubled in the past five years, producing a sense of FOMO among drinkers. But what happens if they just give up?

"Constructive Criticism" is an irregular feature in which I speak frankly about an example of a brewery not meeting their own highest standards. Today I turn my attention to Full Sail and the way in which the brewery's constantly expanding list of bottled products offer variety without much interest.

The words of the day are "hazy" and "juicy," used with abandon to describe hoppy American ales. But what do they actually mean? How is juicy any different than "fruity," and just how opaque must a beer be to be called "hazy?" Let's dig deeper.

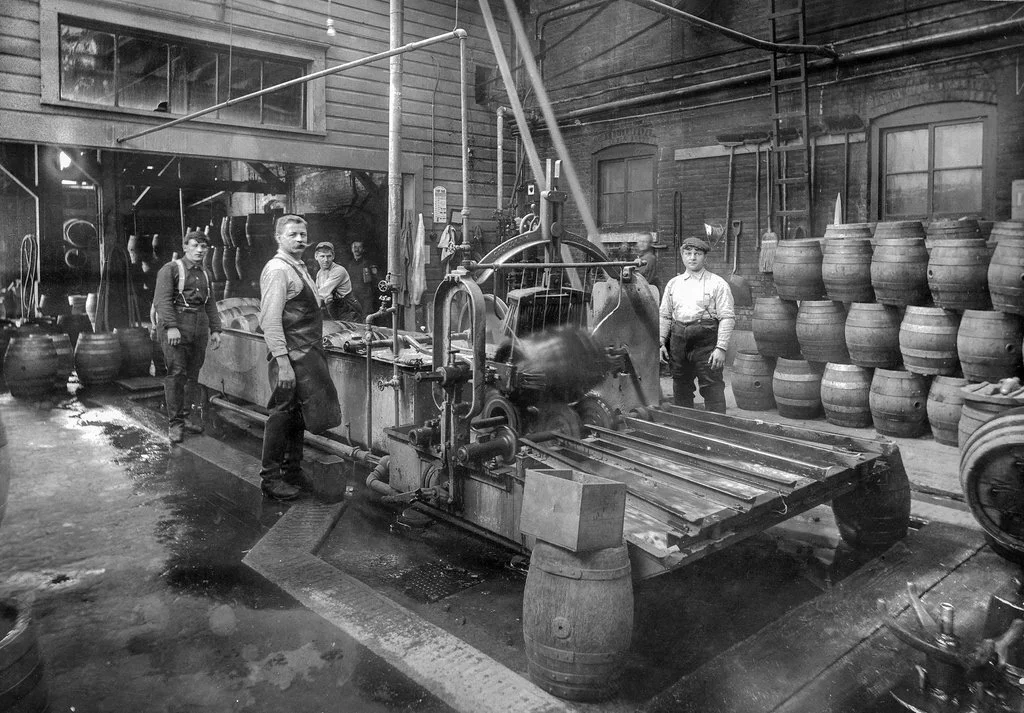

The United States invented modern craft beer. But the model of plucky little brewery set on delivering tasty, handcrafted beer in the face of corporate consolidation is anything but new. A case-in-point is contained in this 29-year-old video, which seems remarkably contemporary.

Time is both atomically precise and experientially relative. We can count off the microseconds and mark events that happened centuries ago--or willl happen centuries from now. But how the time feels is an entirely different matter.

You may not realize this, but it there is an unwritten rule that between Dec 26 and Jan 1, publications (blogs inlcuded) must publish a year-end review. Look, I don't make the rules. If you want me to stop this practice, you have to take it up with the Deep State.

For a writer--well, for me, anyway--the worst outcome is not that people will hate a book (though that's certainly not a good result), but that they won't read it at all. The death of a writer comes not at the hands of an angry public, but an indifferent one.

Breweries all have personalities. Like people, they have a particular appearance, a vein running through their interests, a way of doing things or behaving in the world. But here's the thing: very few actually know what it is.

Yesterday marked the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther's 95 Theses, the Catholic theologian's assault on the church's several abuses of the day. In homage to that event, I turn my own attention to beer and the elements about it requiring their own reform and/or settlement.

It's expensive to enter, winning is a crapshoot, and anyway, there are so many medals that a win is likely to get lost in the shuffle. Most consumers don't track these things, and if they learn a brewery has won an award, probably don't care. All of which raises an interesting question. Why bother?

Here in the awkward moment between seasons, when most of the world has nothing better to do than brace for pumpkin season, there exists a fine moment for think pieces. Into the breach step Boak and Bailey, with one of their typically thought-provoking posts, "Seven Stages of Beer Geek."

We have this very specific number, international bitterness unit, that is invaluable to brewers. It expresses the amount of bittering compounds in a beer. A brewer understands its utility and limitations. All hopped beers have a certain amount of bitterness, and brewers want to be able to measure it. But it has several notable limits.

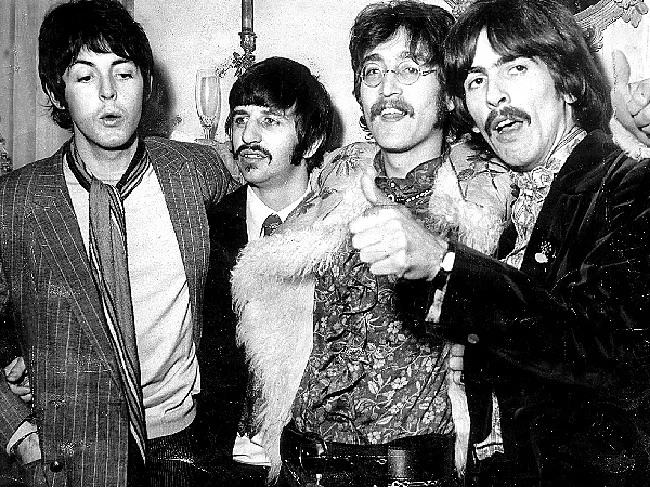

If you've just recently returned from Botswana, there's a small chance you missed the news that Sgt Pepper's Lonely Heart Club Band turned fifty last week. I wouldn't be listening seriously to music until the late 1970s. By that time Sgt Pepper's was an oldie, and all the polyphonics the Beatles deployed were familiar and considered normal.

What do all these details tell us? At the best, they provide accurate information to the small minority of people who know what they mean. At the worst, they provide misinformation. Mostly, though, I think people just tune them out. You really have to know a lot about beer to interpret them and, even then, they are for the most part not that revealing.

In the mid-1990s a new generation of brewers introduced a kind of verve and edginess to beer. This new generation were also tiny, but they were brash and had big ambitions. Some, like Dogfish Head, aspired to transform beer. Sam Calagione was miles ahead of his contemporaries in anticipating that experimentation would one day drive sales. Some, like Stone's Greg Koch, promised to crush big beer. Even when Stone was tiny, he brought the attitude: "you're not worthy," he told drinkers of that old, fizzy yellow lager.

The age of consolidation has surfaced one of the more unusual quirks of the American craft beer segment: the strange morality that has come to pervade it. There's really no other word, either. Morality is that agreement among groups about what is acceptable. It is a self-protective urge, a code to minimize harm either through social norms or ones of purity. It enforces loyalty, which further strengthens the group. Although our friends the 18th-century philosophers tried to argue for a natural or universal morality, it's clear that morality is a purely a social construct that varies place to place. And there is a moral code both craft breweries and craft beer drinkers recognize, as this latest blowback demonstrates.

Assembly Brewing, Portland’s first and only Black-owned brewery, is closing. After just six years, it had become one of the city’s landmark breweries, and owner George Johnson became one of Portland’s most engaging and interesting brewers. It’s a terrible loss.