How to Tank Spectacularly in the New Market

Update. By some cosmic serendipity, Patrick and I went to Corvallis yesterday to record an interview with Tom Shellhammer--a hops researcher and professor in the Fermentation Sciences program at OSU. As we were touring their test brewery, he mentioned how supportive BridgePort has been, and that Carlos Alvarez had cut them a check for $100,000 to support their projects. This doesn't change any of my analysis below, but it certainly adds an important layer to the BridgePort story.

(l-r) John Foyston, Dick Ponzi, Carlos Alvarez

Over at Willamette Week, Matthew Korfhage has an article about Oregon's tightening beer market. The story is an Oregonized version of one we've seen applied to the national market a number of times over the past couple years. Thumbnail: in a tightening market, it's harder for the biggest players to maintain their barrelage even while small and mid-sized breweries continue to post big numbers. This is, in fact, what you'd expect in a mature market and it's not particularly surprising. Korfhage's case-in-point in the article is BridgePort, which is busy imploding before our eyes--but I think this illustrates a different lesson: in a tightening market, a brewery can no longer make a series of stupid decisions and expect to avoid tanking spectacularly.

We have to go back a ways to tell the story. BridgePort is Oregon's oldest extant brewery, and was for the first 20 years of its existence synonymous with the city of Portland. Its flagship beer was named after the city's beloved bird (Blue Heron), it had one of the best pubs in the city--a pilgrimage site for beer travelers. It cemented its connection through things like Old Knucklehead, a barleywine that featured a prominent local beer guy on the label. And then, in 1996, the brewery released its IPA, a beer that changed the course of brewing in Oregon. BridgePort was, ten years ago, one of our healthiest; it sold 24,000 barrels in Oregon, making it the third-largest seller in the state.

But it was about that time that the consequences of a decision made a decade earlier started to become evident. In 1995, Gambrinus, a Texas-based Corona importer, bought BridgePort. It took owner Carlos Alvarez a while before he started tinkering heavily with the direction of his Portland acquisition, but the first real danger sign came when he renovated the pub, turning it into a generically upscale restaurant and destroying one of the company's chief assets.

His next step was to begin tinkering with the beer lineup (only one beer, IPA, survives from a decade ago). This was inevitable and smart, and most breweries have followed a similar course. But BridgePort's approach was haphazard and bizarre.* They killed off brands like Old Knucklehead and Blue Heron that had strong niche followings. They introduced a series of random beers that had no native connection to BridgePort's identity. Some were good (Hop Czar), some not (Cafe Negro) (seriously, that was one of their great ideas). They let the IPA languish. The approach seemed to be: let's release whatever's a year out of fashion and hope to catch the dregs of a wave.

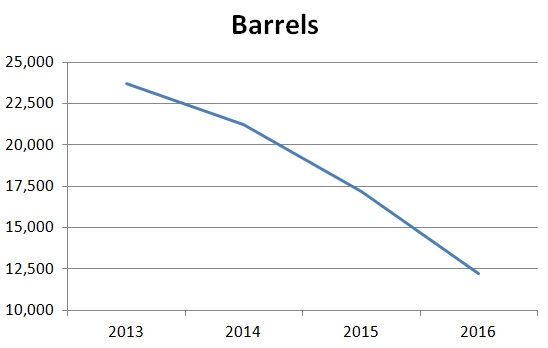

How's that working out? Here's their Oregon sales numbers, via the OLCC:

Three years ago, Alvarez and his executives came up to Portland for a dog and pony show celebrating the 30th anniversary. It was without a doubt the weirdest event I've ever been to. Alvarez was aggressively out of touch with Portland and seemed to go out of his way to emphasize that we were doing it wrong. The restaurant chain Chili's came in for a lot of praise, and that seems to be the model he's attempted to place on BridgePort. He was happy to trademark the word "Beervana" and promulgate the slogan "keep Portland beered," but he seems to dislike anything actually weird. I doubt "Portlandia" occupies a lot of space on the Alvarez TiVo.

In my review of the newly renovated pub back in 2006, I wrote this, rather more hopefully than subsequent events warranted:

“But it is not a classic, nor does it reflect anything intrinsic about the brewery or Portland. Styles will change and so, presumably, will the brewery. In ten or fifteen years, as aesthetics have changed, it will have the dog-earred, slightly embarrassing aspect trendy restaurants inevitably acquire. And then Gambrinus can update it. I hope, for the sake of the brewery and the city, that the company recognizes the beauty and history resident in the massive beams that still span the old warehouse and restore some of the old Portland funkiness. That may seem a long wait, but hey—I recall the brewery of 1991, and it doesn’t seem that long ago. The beams will still be there.”

It turns out that wasn't a one-off; it was a signal of the future direction. And indeed, the pub hasn't aged well.

Craft breweries have to connect to their local market to succeed. There are a few rare exceptions--Rogue sells 84% of its beer outside the state--but even breweries like Widmer and Deschutes depend enormously on local sales. The Texas-based ownership of BridgePort has not just neglected its home market, but seems actively antagonistic to it. Until recently, it was possible for BridgePort to bumble along and still hang onto its local volume, which was basically flat from 2006-2013. But mature markets are not kind to bumblers. Why is anyone going to gamble on a six-pack of ORA (Oatmeal Red Ale) when there are twenty other much safer bets at the store? They're not. The numbers starkly demonstrate this point.

Ten years ago, BridgePort was one of Oregon's best and best-selling breweries. It had the kind of credibility you can't manufacture. It was indelibly connected to the city and seemed to be one of the most stable, reliable breweries in the country. Today it teeters on the edge of failure. If we were running a dead pool now, it would be at or near the top. It's main function now seems to be as a cautionary tale about how not to run your brewery.

_____________________

*Based on conversations with people inside the brewery and direct observation of the way Alvarez treats his employees, I think this comes entirely from San Antonio. I have long admired the work people do at the brewery, who have to turn out quality products in spite of the terrible leadership from above. My criticism is for the decision-makers, not the brewers.