On the IPA Cutting Edge...

No brewery is doing more to push the evolution of IPAs forward than Breakside. (See here, here, and here for recent discussions.) Well, the evolution continues apace. In a recent blog post, head brewer Ben Edmunds writes about some of the things they've been working on recently:

Ben started by noting what the last iteration of Back to the Future experimented with:

Ben continued in his blog post discussing the newer hops they've been using.

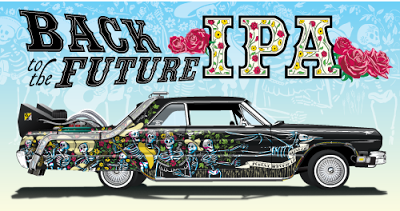

Back to the Future IPA (aka BTTF) is the third release in our series of rotating draft-only IPAs for the year. BTTF is a departure from the previous two releases in the series: Tall Guy IPA and Rainbows & Unicorns. Those two are beers we’ve brewed a number of times and have more or less “set” recipes. By contrast, Back to the Future is a beer that always changes, both each year and– in this year’s incarnations– each batch.Since I am a Serious Journalist (TM), I felt that just quoting extensively from that blog post was inadequate. For true value-added content, you need Ben to elaborate on some of the things he mentions in that post--and I'm just the journalist to cut-and-paste the replies he sent to me via email. All kidding aside, this is cool stuff and worth your attention. Even a beer so dominated by a single ingredient can be inflected by other ingredients and techniques. Ben discusses the way flaked grains, water treatments, new hop varieties, and yeast strains can transform an IPA. Read on...

Ben started by noting what the last iteration of Back to the Future experimented with:

Specifically, we used BTTF 2015 to explore some questions we had about the use of flaked grains in IPAs. We also trialed a much softer water profile than we normally use with our IPAs. As with any trial, there were parts of the 2015 version that we liked and learned from, and elements that we didn’t. The things that we liked are now incorporated into many of our other hoppy beers. Both Lunch Break and Tall Guy use a good portion of flaked barley in the malt bill, for example. The hops that we used BTTF 2015– Ella and Azacca– have both found a home in our hop schedules for several other beers, including Hop Delivery Mechanism and Imperial Red.To which I asked about both the flaked grains and soft water. Ben comments:

I think there is a lot of emphasis amongst brewers these days, especially East Coast brewers, on flaked grains. They tend to use a lot of wheat and oats. We'll use all three (as well as flaked corn and flaked rice, in other beers) in hoppy beers, but I think we tend to use flaked barley more than the other flaked grains because of its more neutral character. Flaked wheat and flaked oats are great but tend to be very characterful; flaked corn (which we use in our Coconut IPA) and flaked rice (Rainbows & Unicorns) are also great. They all help round out body with some light grain character that allows hops to shine.Water is something I need to address seriously at some point. When I was speaking with Nick Arzner on Friday, he mentioned this issue as well. He'd just done a collaboration with Great Notion. He also mentioned that they go for heavy chloride in their water to soften the palates of their "New England" IPAs. This, Nick suggested, was one of the most important ways these beers were distinguished from West Coast IPAs.

Softer water is still a subject of debate within Breakside. Generally, we have come to favor a slightly Burtonized water profile for most of our hoppy beers. When we first opened, I used a classic Burton ratio (10:1 sulfate-to-chloride) on most hoppy beers. Over time, we've backed off on that in an effort to allow the finish to come off a little softer and let the hop flavor linger into the aftertaste. Most of our core beers are still 5:1 sulfate-to-chloride or higher (Wanderlust, Breakside IPA, and IGA are all pretty Burtonized at 8:1), but many of the new recipes we've worked on go down to the 3:1 range. We have tried a few pub beers with a very soft water profile (no Burtonizing or a chloride-heavy profile), and that gets a little flabby for our own preferences. BTTF uses the 3:1 profile, which, in my mind, optimizes hop flavor and a refreshingly snappy finish.

Ben continued in his blog post discussing the newer hops they've been using.

This year, we’ve revived BTTF in the same spirit, brewing it with combinations of hops that we think have a lot of promise and using this beer as an opportunity for us to explore some “new directions” in making IPAs. Distilling it down to 3 key areas, this year’s Back to the Future IPAs are exploring the following territory: Pairing a new and interesting hop (Topaz, Lemondrop, Idaho 7) with hops that are already beloved (Mosaic, Citra, and Ella). Each batch of this beer focuses on a different combination of those hops. The first batch, which is currently on the market, is heavy on Topaz and Mosaic. The second round of brews will be mainly Citra and Lemondrop. The final batches– the ones that will be hitting the market in August– will use Ella and Idaho 7.I know that the brewers at Breakside have novel hopping regimes based on whether they think a hop is "punchy" (spiky, sharp flavors) or "soft." I asked him how these new hops behaved.

Topaz is a lot like Galaxy but without the intense stone fruit character; it comes off as a little waxy/petrol the way many Southern Hemisphere hops do, but it has some nice underlying tropical notes. Lemondrop is very citric, as advertised-- kind of like a super Cascade. And Idaho 7 is reminiscent of a softer Centennial-- lots of lemongrass and Fruity Pebbles for me. Culmination uses it a lot in their Urizen Session IPA. I'd say that Topaz is very punchy, Idaho 7 pretty punchy, and Lemondrop soft.Finally, Ben talked about the interplay between yeast strains and hop expression. He writes that Breakside is "using a different yeast strain with this beer this year, and it seems to respond to American hops differently than our normal house ale strain." This is not just a matter of the way different flavors inflect each other, like blending colors. There's an actual biochemical process that happens in which hop compounds are transformed during fermentation--an issue I've written about recently. Ben expanded:

I think that the most interesting part of this whole experiment might be the use of a non-traditional "West Coast" yeast, much in the same way that the East Coast guys are favoring English yeasts for their IPAs. There's some real digging to be done about yeast selection and the future of American IPA.So