Cider Saturday: The Climate of Cider

File this under "hmmm." When I traveled to England, France, and Spain in January to do cider research, I was amazed at how consistent the weather was. I'd pull up my weather app, which was set to Portland, OR, and it would say 42 degrees Fahrenheit and rainy. Then I'd swipe over to Bristol (which is a decent midpoint between Hereford and Somerset), and it would say 42 and rainy. Then to Lisieux and it would say ... 42 and rainy. As I write this, it's 53 in Portland, 56 in Bristol, and 57 in Lisieux. (All cloudy, natch.) It got me thinking about climate and whether there was something to wet, temperate places that make for good apples.

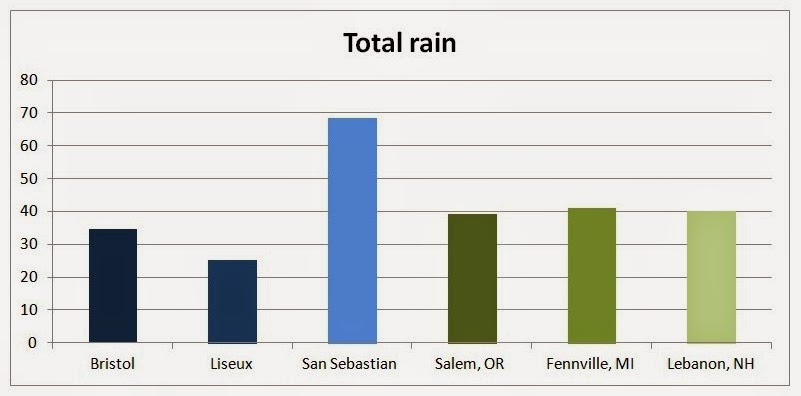

In the book I'm working on, I have used a narrative model to describe cider, focusing in on traditional cider makers from various places in Europe and the US. In the charts below, you can see how they stack up in terms of temperature and rainfall. I selected the places based on the cideries I covered in my book, throwing in Fennville, Michigan as a final entrant, even though I didn't visit Virtue Cider. It's on the coast of Lake Michigan. (I did speak with Greg Hall and the cidery is mentioned in the book.) You could add a lot more lines to the chart--Oviedo, Asturias, Yakima, Virginia--but this seems to illustrate things well enough.

Let's look first at average high temperatures, which are relevant during the growing season. At the height of the growing season, there's a ten-degree difference between England (72) and all the US locations, which interestingly have average highs of 82. That's the widest gap. Spring temps are warmer in Spain, but similar in the other locations.

I was especially interested in the lows, because in traditional cider-making, the juice is fermented naturally. Temperatures that are too low would halt that process without intervention, while high temperatures would put the ferment at risk. (All the Europeans do natural fermentation, as do EZ Orchards in Salem, Virtue in Fennville, and although Farnum Hill pitches yeast, they don't have much temperature control.) Michigan and New Hampshire are real outliers here, but Oregon and the European countries stay largely within a few degrees of one another.

Finally, rainfalls are pretty similar, too, except for insanely wet San Sebastian in the Basque Country, which is a wetter city than New Orleans. The rainfall patterns are different: Oregon's dry in the summer, Bristol in the Spring, and Lisieux in the winter. San Sebastian is never dry, and New Hampshire and Michigan get fairly even precipitation throughout the year.

It's not easy to draw big conclusions, but I pass it along for your edification nevertheless.

In the book I'm working on, I have used a narrative model to describe cider, focusing in on traditional cider makers from various places in Europe and the US. In the charts below, you can see how they stack up in terms of temperature and rainfall. I selected the places based on the cideries I covered in my book, throwing in Fennville, Michigan as a final entrant, even though I didn't visit Virtue Cider. It's on the coast of Lake Michigan. (I did speak with Greg Hall and the cidery is mentioned in the book.) You could add a lot more lines to the chart--Oviedo, Asturias, Yakima, Virginia--but this seems to illustrate things well enough.

Let's look first at average high temperatures, which are relevant during the growing season. At the height of the growing season, there's a ten-degree difference between England (72) and all the US locations, which interestingly have average highs of 82. That's the widest gap. Spring temps are warmer in Spain, but similar in the other locations.

I was especially interested in the lows, because in traditional cider-making, the juice is fermented naturally. Temperatures that are too low would halt that process without intervention, while high temperatures would put the ferment at risk. (All the Europeans do natural fermentation, as do EZ Orchards in Salem, Virtue in Fennville, and although Farnum Hill pitches yeast, they don't have much temperature control.) Michigan and New Hampshire are real outliers here, but Oregon and the European countries stay largely within a few degrees of one another.

Finally, rainfalls are pretty similar, too, except for insanely wet San Sebastian in the Basque Country, which is a wetter city than New Orleans. The rainfall patterns are different: Oregon's dry in the summer, Bristol in the Spring, and Lisieux in the winter. San Sebastian is never dry, and New Hampshire and Michigan get fairly even precipitation throughout the year.

It's not easy to draw big conclusions, but I pass it along for your edification nevertheless.