The Third Dimension: Wild

A little while back, we had a lively discussion about whether Americans should call their wild ales "Lambics." The question was taken up on Twitter and Reddit as well, and one of the most pervasive critiques was summed up by commenter Jordan like this: "At least supply a catchy name for the new style if you're going to insist on the semantic distinction." Fair enough.

Let's begin by agreeing that aside from these wildlings, beers can be divided pretty cleanly into the categories of ale and lager. (There are outlying opinions, but let's dance past them for brevity.) This taxonomical division rests on the behavior of the yeasts, so why not follow the logic and add a third category of wild ales*. These are the beers acted upon by any rough interloper (brettanomcyes, lactobacillus, pediococcus, etc.) in any method of brewing. The category would then include anything from Berliner weisse to lambic, Flanders tart ales to whatever it is Chad Yakobson is making.

The thing is, there are a lot of ways to get to funky, and the extremely baroque procedures of lambic-makers are only one. A possibly inexhaustive list includes:

So that's my modest proposal. Place them all in the category of wild ales, as distinguished from ales and lagers, and pay special attention to those beers that use fully spontaneous methods of fermentation.

Errata.

It's really easy to get in the weeds here. Rodenbach, for example, calls its method "mixed fermentation," and uses a version of barrel inoculation of fresh beer. Ah, but those barrels were originally inoculated by beer fermented spontaneously, a practice Rodenbach only discontinued in the 1970s. So it's in a sub-category of probably one brewery. But whatever else Rodenbach is, it's definitely wild.

___________________

*Pedants may point out that "ale" indicates saccharomyces, and the beers of Crooked Stave are made exclusively with brettanomyces, so therefore Chad is not making wild ales. I say those pedants take it to BeerAdvocate, where such hair-splitting is encouraged.

|

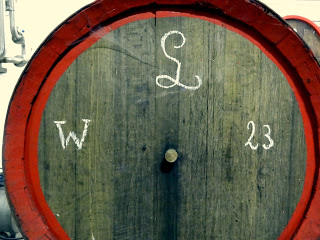

| Each lambic brewery has unique markings so blenders can distinguish them. This is Boon's. |

The thing is, there are a lot of ways to get to funky, and the extremely baroque procedures of lambic-makers are only one. A possibly inexhaustive list includes:

- Spontaneous fermentation. Leaving aside things like turbid mashes and extra-long boils, what makes this the most extreme and rare form of wild ale is the method of fermentation: naked wort exposed to the elements. The resulting bacteriological bacchanalia is wholly uncontrollable and few brewers actually rely on pure natural fermentation. Allagash did the world an enormous favor by inventing a word for this process, and we should stick with it. All lambics are spontaneous wild ales, but not all spontaneous wild ales are lambics.

- Spontaneous via media. Cideries and wineries use this method all the time. Yeast collects on the surface of fruit, and is adequate to ferment wine and cider all by itself. I know of only one brewery that does it--Italy's LoverBeer, where brewer Valter Loverier uses local Barbera grapes to inoculate his wort. It makes such spectacular beer, I wouldn't be surprised to see others follow along.

- Solera. In the production of balsamic vinegar and certain liquors like sherry, a solera consists of a series of wooden casks. In beer production, each cask is its own solera. New Belgium is the most famous solera brewery. When it comes time to produce a beer like La Folie, the master blender will begin tasting lots from different vats and making a mother blend. Afterward, the brewery tops each vat off with fresh beer and the process repeats. Over time, each vat becomes a distinct ecosystem for populations of different microorganisms, and the beer each one produces is different from the next.

- Barrel inoculation. Another way of working with native populations of yeast and bacteria is to nurture them in barrels and inoculate fresh wort by putting it in inside these funky casks. Some breweries regard this as spontaneous, but it's a form of indirect pitching--especially in cases in which the brewery has seeded the barrel with a batch of brettanomyces-pitched beer.

- Pitched wild yeasts. The easiest and most common way to introduce wild yeast and bacteria to fresh wort is in the form of laboratory-produced pure culture. At some point, people are going to debate whether these constitute "wild" strains, but so far, we haven't had to contend with that argument. (Knock on wood.)

So that's my modest proposal. Place them all in the category of wild ales, as distinguished from ales and lagers, and pay special attention to those beers that use fully spontaneous methods of fermentation.

Errata.

It's really easy to get in the weeds here. Rodenbach, for example, calls its method "mixed fermentation," and uses a version of barrel inoculation of fresh beer. Ah, but those barrels were originally inoculated by beer fermented spontaneously, a practice Rodenbach only discontinued in the 1970s. So it's in a sub-category of probably one brewery. But whatever else Rodenbach is, it's definitely wild.

___________________

*Pedants may point out that "ale" indicates saccharomyces, and the beers of Crooked Stave are made exclusively with brettanomyces, so therefore Chad is not making wild ales. I say those pedants take it to BeerAdvocate, where such hair-splitting is encouraged.