IPAs Have Conquered America, But Why?

In response to yesterday's IPAs in America post, one beeronomist (there are others) noted:

Well, I'm glad you asked, Patrick, if only because it allows me to stretch the discussion out--bloviate--over two posts. In fact, I do have a theory, and it's built, like all great blogging theories, on a single anecdote that I garnish with actual data and a bit of fairly accurate history to create my wholesome meal of an answer.

So here's my theory. In the age before craft (BC), we had a lot of ideas about beer. We believed "less filling" was a higher state of beer. We feared "bitter beer face." We had never heard of ales, never mind "styles," and considered Heineken impossibly strong and exotic. Also, beer tasted bad. There was a hollow tinniness to it, and the aftertaste was slightly unpleasant. (I have no data to back this claim, but make it I shall: I suspect beer in the 70s was pretty bad, never mind how many hops it had, and that the technical quality and consistency of macro lager is very high today by comparison.) You muscled your way through a beer to get to the next one and, if you persevered, the fourth one down the line.

We were ignorant. On the one hand, we were told bitter was bad--seemed logical enough--but on the other, beer companies had essentially made it impossible for us to know what hops tasted like. We never associated the two. Now we enter the period after craft (AC) and for the first time taste hoppy flavors like grapefruit, lavender, and marmalade in our beers. They're not bad! In some very abstract way, we can see how they might be called bitter, but it's not nasty bitter, tin bitter; it's single-estate-Ethiopian-dark-roast-with-notes-of-blueberry-and-black-pepper bitter.

Those who came to craft beer were a self-selected sample of people who didn't like mass market lagers. Axiomatically, they were looking for something different, and along each dimension, IPAs offered a contrast: they were strong, they were fruity and ale-y, and of course, they were intensely-flavored. There was a reason even very hoppy pilsners didn't take off--they were too familiar. It had to be more than just hoppy. The fullness and fruitiness of ales were a revelation. But hops were key, and American hops, absolutely unfamiliar and even a little bit bizarre, were a big part of things. Bolted to the chassis of a nice, full ale, they created flavors that seemed unrelated to beer from the land of sky-blue waters. We were thrilled.

The rise of IPAs is similar both in pattern and kind to what was happening in artisanal food and beverage segments elsewhere. When pursuing coffee, cheese, whisk(e)y, and wine, people went for the intense; they offered the best contrast to the bland, mass-market products they had grown up with. In cuisine, "ethnic" foods (which are of course "foods" to people in different countries) have led a renaissance since the 70s and 80s, and we're forever looking for the next great flavor around the corner.

Looking back, it seems inevitable that a strongly-flavored beer was going to become king. That it was IPA and not, say, tripels, is a little dicier to explain. We are left to speculate. American hops, once derided in other countries, have won the test of time. Everyone now agrees: they're awesome. So saturated IPAs are objectively tasty. I also wouldn't underestimate the value of their being local. I haven't figured out why this matters, but country after country, region after region, it seems to. And finally, trends build on themselves. IPAs may have won out partly because they started to get popular before people were exposed to Belgian styles and sour ales.

And that brings us to the end of my tale of Why IPAs Conquered America. Surely you have your own theories and refutations, and as always, I welcome them in comments--

I dunno, seems like false advertising - have you answered your question, 'how'? I get it that they have [conquered America] but I was expecting your usual bloviating - er - erudite analysis of why IPA is especially right for American palates. What is it about the IPA and the American Experience that makes them so simpatico? (My bold)

|

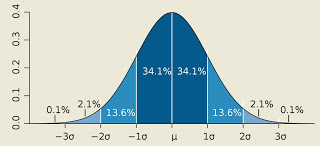

| The purpose of this image will become evident in due course. |

The Anecdote

Way back in the waning days of the last century, I worked on a fantastic research project at Portland State University. We were attempting a massive effort to interview parents and children and their social workers in the state child welfare system. We worked like fiends and grew quite close. At a certain point, our very cool boss started arranging post-work happy hour get-togethers where we could chat about work and blow off steam. I had just begun writing about beer on the side, and so was regarded as the local expert. The waitress came, ran through the tap list, and the Very Cool Boss asked which beer to order. I asked what kind of beer she liked. She said: "I don't like bitter beer. I like IPAs."

The Data

We are all well aware that industrial lager producers have been trying to make their beers as inoffensive as possible for the better part of a century. Products made for mass audiences must have no sharp edges or challenging dimensions. Humans crave sweetness and so food companies sweeten foods like pasta sauce that have no business being sweetened. Over the years, the beer companies have done the same thing by steadily removing hops. They now fall below the human threshold for flavor.

The History

Craft brewing arose as a reaction to the homogenization and boring-ification of mass market lagers. It was sparked by people who existed way out in the tail on the beer-styles bell curve, people who loved intense, rich flavors. For a long time, craft brewers thought they had to create bridges between their beer and Hamm's, so they dabbled in Vienna lagers, wheat beers, and fruit ales. This buoyed craft brewing through the 80s, but by the 90s, people were losing interest in tame craft beers (and also bad beers, of which there were a growing number). The market stumbled and took several years to recover. When it did, it was on the strength of beers like IPAs that were sharply different from mass market lagers.So here's my theory. In the age before craft (BC), we had a lot of ideas about beer. We believed "less filling" was a higher state of beer. We feared "bitter beer face." We had never heard of ales, never mind "styles," and considered Heineken impossibly strong and exotic. Also, beer tasted bad. There was a hollow tinniness to it, and the aftertaste was slightly unpleasant. (I have no data to back this claim, but make it I shall: I suspect beer in the 70s was pretty bad, never mind how many hops it had, and that the technical quality and consistency of macro lager is very high today by comparison.) You muscled your way through a beer to get to the next one and, if you persevered, the fourth one down the line.

We were ignorant. On the one hand, we were told bitter was bad--seemed logical enough--but on the other, beer companies had essentially made it impossible for us to know what hops tasted like. We never associated the two. Now we enter the period after craft (AC) and for the first time taste hoppy flavors like grapefruit, lavender, and marmalade in our beers. They're not bad! In some very abstract way, we can see how they might be called bitter, but it's not nasty bitter, tin bitter; it's single-estate-Ethiopian-dark-roast-with-notes-of-blueberry-and-black-pepper bitter.

Those who came to craft beer were a self-selected sample of people who didn't like mass market lagers. Axiomatically, they were looking for something different, and along each dimension, IPAs offered a contrast: they were strong, they were fruity and ale-y, and of course, they were intensely-flavored. There was a reason even very hoppy pilsners didn't take off--they were too familiar. It had to be more than just hoppy. The fullness and fruitiness of ales were a revelation. But hops were key, and American hops, absolutely unfamiliar and even a little bit bizarre, were a big part of things. Bolted to the chassis of a nice, full ale, they created flavors that seemed unrelated to beer from the land of sky-blue waters. We were thrilled.

The rise of IPAs is similar both in pattern and kind to what was happening in artisanal food and beverage segments elsewhere. When pursuing coffee, cheese, whisk(e)y, and wine, people went for the intense; they offered the best contrast to the bland, mass-market products they had grown up with. In cuisine, "ethnic" foods (which are of course "foods" to people in different countries) have led a renaissance since the 70s and 80s, and we're forever looking for the next great flavor around the corner.

Looking back, it seems inevitable that a strongly-flavored beer was going to become king. That it was IPA and not, say, tripels, is a little dicier to explain. We are left to speculate. American hops, once derided in other countries, have won the test of time. Everyone now agrees: they're awesome. So saturated IPAs are objectively tasty. I also wouldn't underestimate the value of their being local. I haven't figured out why this matters, but country after country, region after region, it seems to. And finally, trends build on themselves. IPAs may have won out partly because they started to get popular before people were exposed to Belgian styles and sour ales.

And that brings us to the end of my tale of Why IPAs Conquered America. Surely you have your own theories and refutations, and as always, I welcome them in comments--