The Birth of a Romantic Fact

A couple years back, John Holl and I were drinking beers at The Commons when the topic of "romantic facts" came up. Romantic facts? You know, those (false) stories that have gotten repeated so often they've come to be accepted as truth. Ben Franklin saying "Beer is proof God loves us," or the one about how a monk smuggled yeast into Bohemia from Bavaria to brew the first pilsner--those kinds of things. In journalism there's a concept about a story that's too good to fact check, and the romantic fact is beer's version of that.

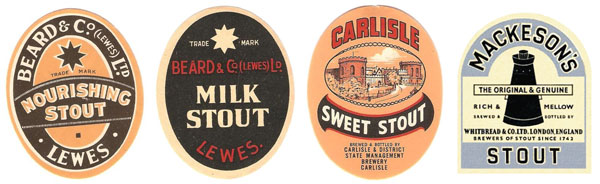

How do these things get started? Lots of ways, including bad scholarship, misunderstanding, and--my favorite--marketing gloss. Ron Pattinson has turned his attention to milk stouts this week, uncovering a style basically invented on a romantic fact. Milk stouts were a subtype of the "nourishing stout" category that flourished in Great Britain at the end of the 19th and beginning of 20th century. The whole phenomenon is fascinating. In the late 1800s, stouts--which by that time had grown weaker in strength--were becoming associated with healthfulness. This appears to have started with doctors, who recommended them as a restorative. Breweries, sensing an opportunity, began promoting them as healthy, adding things like oatmeal, oysters, sugar, and in one (gross) case, meat. They were variously called "nursing stouts" (recommended for nursing mothers), "ladies' stout," and even "invalids' stout."

“The energizing carbo-hydrates of a glass of milk in a pint of stout. Anti-rheumatic, energizing. Recommended by the medical profession.”

Milk stouts were a later arrival to the genre, introduced by Mackeson's Brewery of Kent around 1907. By that time the association between health and stout was unshakable, and breweries were busily capitalizing on it. Ron quotes a fantastic article published not long after Mackeson released the beer describing its origins--and it is absolutely packed with romantic facts ("stout particularly, because it is an invalids' drink"). They're amusing now only because we understand science better and wouldn't be fooled by such silly claims. But that very understanding makes this a perfect case study in how romantic facts get started.

I encourage you to go read the whole piece, but I'll quote a few choice pieces here by way of demonstration. The article, published in the Folkestone, Hythe, Sandgate & Cheriton Herald in 1909, quotes liberally from some unnamed source at the brewery, who unspools this tall tale about a "worker in food chemistry" who set them on the course of milk.

“This gentleman was introduced to us by a very large firm of milk food manufacturers, and very heartily he entered into our ideas. We explained what wanted, and in double quick time he shewed that many fond notions were impossible. Meat? That cannot added to malt liquors because of the danger of ptomaine poisoning, and if confine ourselves to extracts we get only the flavour, and no goodness. Eggs?: Impossible again, for many reasons, equally good. Milk? Well, milk is a food of foods - five complete foods in one — and our friend thought that there was hope here."

Did such a man actually exist? Did Mackeson really consider meat and eggs (Ron doubts it). Who knows? The article-writer guilelessly passed it along, doing fine work for the brewery's marketing team. The piece continues:

“His methods were and instructive. Stout is a tonic — an appetiser and an energiser. You don't want stout to make you fat, or to give you heat — stout must not be ‘heating' or ‘fattening,’ and so you can’t put the cream into it. That disposes of one part of the milk. Then you don’t want to make flesh by drinking stout. No. If you want to grow fleshy you drink the stout - that gives you an appetite, and the appetite will see to the flesh-forming in Nature's own way. So away goes a second part the milk, the casein. Then you don’t want the milk fluid — the water — because that is an adjunct the stout itself. So with the fat, the casein, and the water removed, you have only the salts and the lactose left. It interesting to see that milk contains 75 percent of mineral salts, eleven in all; many them are natural water salts, and they would possibly interfere with the ‘balance' of the ‘water' which is such an important factor in all brewery work.

“But the lactose — the sugar of milk — that struck our friend. He found that it could be added to malt liquor without changing the colour, appearance, or taste."

I don't mean to be harsh--selling snake oil is still a jillion dollar business, and concepts like the paleo diet are no more plausible than "heating." But basically nothing in these paragraphs seems even remotely true. This careful consideration of the constituents of milk by a food chemist is the kind of grade-A hogwash companies put in their ad copy today. It's not meant to be taken literally. When a soda company suggests their carbonated sugar water will bring peace on earth, or a beer company hints that light beer will bring in the babes, even the dullest of consumer understands what's going on.

No one would consider a milk stout "healthy" today--or, in any case, more healthy than any beer. The "fact" part of this romantic fact seeped away over the course of the scientific century since the article emerged. But it illustrates how these things come about: 1) a claim is made; 2) it enters the press, which is considered an objective source; 3) it goes uncontested within the source; 4) time passes and modern readers assign the source special credibility because it was contemporaneous with the "fact" in question; and finally, 5) it gets repeated by subsequent, supposedly reliable sources, congealing as "fact." That writers on the subject of beer have never been the most scholarly types hasn't helped.

The "milk stout is healthful" claim was interrupted before stage four because modern readers have their own information to dispute it. So often that's not the case, particularly when the original claim describes a past event. Here we see the romance in the fact and are charmed by its quaint silliness. Nursing mothers prescribed milk stout--hilarious! But it's also a perfect illustration of why we should cast a gimlet eye at any and every old "fact" we know about beer. The more romantic they are, the less likely they are to be fact.